The Lübeck Dance of Death

Remember that you will die one day

In the midst of life

- we are surrounded by death

On this page

By Hildegard Vogeler and Hartmut Freytag

To dance

The famous Lübeck Dance of Death was created by the young Bernt Notke in 1463, modelled on the Danse Macabre in Paris from 1424/25 for the Confession Chapel in the north of St. Mary's Church. This side facing away from the light suggests the idea of death and reminds people to organise their lives in accordance with Christian teaching through repentance, confession and penance. At the time, people were expecting the plague to spread from the south, which actually reached Lübeck at Easter 1464.

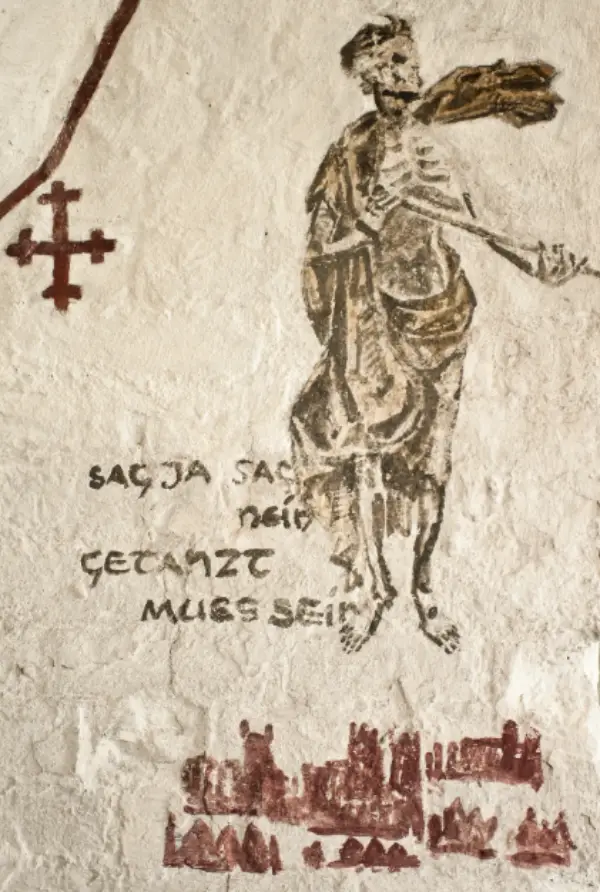

The Dance of Death was not painted on wooden panels, but on a 26 metre long and almost 2 metre high canvas wall covering, which stretched along the walls of the chapel above the confessional as a continuous sequence of pictures. Led by a flute-playing Death and a coffin-carrying Death, the frieze depicted 24 almost life-size pairs. They each consisted of a death figure and a (still) living person, starting with the pope and the emperor, the mayor and the merchant through to the farmer and the cradle child. The round dance comprised representatives of all social classes and included individual female figures and different age groups. The living only joined in the dance of death rigidly and reluctantly, while the skeletons of the dead leapt wildly and exuberantly. In the end, however, a scythe-wielding Death mowed down all life.

The fact that the macabre round dance takes place directly in front of the local landscape with the representative city backdrop of Lübeck at its centre distinguishes the Lübeck Dance of Death from all other traditional dances of death. Viewers can identify with the figures in the round dance and recognise that a mirror is held up before their eyes here and now, in which they see themselves dancing with death. In the face of death, the transience of power, wealth and beauty in this world is revealed.

The Low German text with the dialogue between the figures of death and the living unfolded beneath the figures in a similarly artful way to the colourful sequence of images in the painting. The Dance of Death reminded the individual to orientate his life towards the afterlife and redemption on the one hand, and to commit himself to his personal task within the social community in this world on the other.

The Dance of Death in St Mary's has a "sister piece" in the Nikolai Church in Tallinn (Estonia), the Revaler Totentanz. This was created by Bernt Notke around 1500, modelled on his Lübeck Dance of Death frieze. With 13 figures, this fragment, also painted on canvas, forms the beginning of an originally complete Dance of Death. The dynamism of the figures and the luminosity of its colours still give an idea of how expressive the old painting in Lübeck must have been.

The delicate wall covering of the Lübeck frieze was frequently repaired over the years and was finally so worn out in 1701 that the entire painting was replaced with a copy by the church painter Anton Wortmann. At the same time, the deserving city poet Nathanael Schlott created a contemporary, stylised new verse, which, as in the old Dance of Death, was placed in the same position below the figures. The new verses conveyed a changed understanding of death, as the baroque longing for death replaced the joy of life and fear of death and the Last Judgement, which was characteristic of many of the figures in the late medieval work.

The Dance of Death of St Mary's has continued to have an impact since its creation right up to the present day. Traditional and new forms of this type of art bear witness to this, especially when wars, epidemics and other catastrophes evoke a feeling of fear and powerlessness in the face of overwhelming forces. It is precisely at such times that people seek and find an expression of their existential mood in the dance of death.

The Lübeck Dance of Death was completely destroyed during the Second World War. Today, two more recent artistic realisations in the Dance of Death Chapel keep the theme of death and the Dance of Death alive. One is the two towering Dance of Death windows by Alfred Mahlau on the north wall and the other is the semi-circular window by Markus Lüpertz above the north portal of the chapel.

Mahlau designed his work in 1956/57 in memory of the destroyed frieze. He was inspired by the old figures. As a memorial to the Second World War, he placed the round dance of death above the burning houses and towers of the city of Lübeck. However, the painter reinterprets this catastrophic scenario as a vision of peace, offering consolation; he interprets the cradle child at the end of the round dance of death as the Christ child in the manger, who overcomes death and raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing. The statement culminates in the words "GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO. AMEN" (Glory to God in the highest. Amen).

The window, designed by Lüpertz in 2002, combines familiar Christian symbols of death and resurrection: the fish as a symbol of Christ, the skull in dialogue with the dove of peace, which holds a blossoming red rose in its claws as a symbol of love and life, the blue jug with the water of life, the snail as a symbol of death and rebirth and the seven torches of the Apocalypse, which herald the Last Judgement. Seen in this way, the picture window is not a vision of horror, but a hopeful and comforting interpretation of death.

Literature:

Der Totentanz der Marienkirche in Lübeck und der Nikolaikirche in Reval (Tallinn). Edition, Kommentar, Interpretation, Rezeption. Hrsg. von Hartmut Freytag (Niederdeutsche Studien 39), Köln - Weimar - Wien 1993.

Zens, Der neue Lübecker Totentanz, Hrsg. Galerie Peithner-Lichtenfels, Wien [2003].

Death

For many adults, dealing with death and dying is one of the few remaining social taboos. We are very reluctant to talk about it. In many cases, not even our closest relatives know what we want for our end. The aim is to remain young, dynamic and active for as long as possible. This is sometimes called youth mania. And current research suggests that this is becoming increasingly achievable. "Homo Deus" - it is becoming conceivable that human decline and illness will be medically surmountable in a few decades. At the same time, the hospice movement and the social debate on topics such as living wills have set an opposite movement in motion. A movement that is very important:

If our loved ones know our wishes regarding the end, then we enable them to have the reassuring feeling of being able to arrange everything in our favour when we say goodbye.

And yet something remains to be done. What would it be like if death and dying themselves lost some of their horror? Because we have images of them that do not frighten us. Because we look beyond the suffering to what we believe awaits us after the threshold of death. Just as J.K. Rowling has Albus Dumbledore say: "After all, for the well-prepared mind, death is just the next great adventure." We can learn from the children here. And I find that very biblical: we should receive the kingdom of heaven like children. Children do not yet realise that topics relating to dying and death are social taboos. They express what is on their minds without filters or self-censorship. They divide their grief into portions that they can cope with. And so it can happen that they cry inconsolably over a loss one moment and then play happily again the next. I would like to encourage this: That we dare to learn from the children. That we allow ourselves to be afraid. That we allow ourselves to develop images of what comes after death. And that we dare to talk about it with our own ideas and with the thoughts that people from art and history have had about it over the centuries.

(From St Marien's pastor Inga Meissner)

Life

Where do I come from? Where will I go? How can I live? The Gothic basilica of St Marien has reflected the fundamental questions of human existence in an unrivalled way since the 13th century. Questions that have preoccupied people of every generation. The sublime medieval processions in the cathedral's liturgical celebrations, the processions in white robes with precious jewellery, the stylised rituals with their distancing habitus were given the democratisation of the goal of life as an artistic addition:

The Dance of Death simultaneously depicts the fear of the end as well as the perspective of equality of all outcomes.

With the Dance of Death, the cathedral thus unfolds the satirical vision of a deep consolation that urges every life to take shape. What a design! One can imagine how the trembling faithful entered the confession chapel, the monumental wall frieze and thus the deep gravity of the situation before their eyes - only to be assured of the forgiveness of their sins. This meant nothing less than the continuation of life. The fascinosum et tremendum, as described by Rudolf Otto in "Das Heilige" (The Sacred), perhaps the most important work of religious studies of the last century, is evident here.

Faith first responds to the final questions of life with respectful perception and interpretation of the reality of life - in order to admit that, as a human being, we can only ever shudder and be comforted. Just as the Antwerp altar in St Marien shows with its depiction of the death of the Virgin Mary: A comforted death. Death as a transition to the other life, of which we know nothing and hope for nothing but peace.

(From St Marien's pastor Robert Pfeifer)

In the midst of life we are surrounded by death

At first glance, the Dance of Death seems quite strange or even disturbing. But when you look at it and read the texts for longer, you become more thoughtful. And then all of a sudden: so incredibly grateful for these breaths that call themselves life.

Samuel Stahn

Volunteer